I don’t know about you, but I remember being spoon-fed a particular story in early October while I was in elementary school. It went something like this: in 1492, Queen Isabella of Spain pawned her jewelry to finance Christopher Columbus’ voyage to prove that the Earth was round and, in so doing, establish a more efficient trade route with the Indies for spices, but instead he discovered the New World! There were even a few little songs and, of course, a whole extra day added to the weekend. It was pretty cool. It’s also complete bullshit. All of it. Even what we think the names of the ships were that made that first voyage are wrong.

First of all, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand didn’t have to scrounge loose change together to bankroll Columbus’ excursion. On top of decades of financial reform led by Queen Isabella, the king and queen had just defeated the Muslim kingdom of Grenada in modern-day southern Spain. They weren’t exactly hurting for funds. There’s also this little discrepancy: in the late 15th century, almost no one in Europe held the belief that the Earth was flat. While it is true that during the Middle Ages Europe saw a rise in folks believing the Earth was flat, by Columbus’ time Europe had experienced a collective jogging of memory. The idea that Columbus proved the Earth was round came out of a fictional work by Washington Irving.

So, no: Columbus wasn’t out to prove the Earth’s shape. He was clearly confused about the size of the planet, though, as he argued he could reach Southeast Asia by sailing two-thousand miles west. Even had there not been two whole continents blocking his path, he’d have come up pretty short. And, yes, he was out to establish a more efficient trade route, though his motives for wanting to do so are up for debate: surely, the amassing of wealth was a solid motivator (he was contractually granted ten percent of any profits from the venture) though some contend (including the Knights of Columbus) that Columbus was a pious man and was ultimately looking to undermine Islam and fund another Crusade. Even if he had not, himself, been motivated by piousness, it does not strain credulity to think that he may have used such justification to sell King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella on the prospect: let’s not forget that these were the same folks who established the Spanish Inquisition.

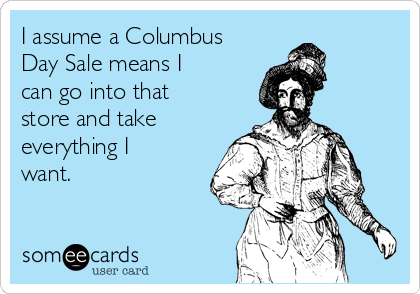

Then there’s the whole “discovery” thing. Even if he had been successful and made his way to Asia, he could, at most, be credited with discovering a new route. Columbus discovered exactly diddly-squat. Calling Columbus’s lucky break – stumbling into a heavily populated land mass that he hadn’t previously known about, in the midst of his monumental navigational failure – is about as big of a whopper as the claim that Edison invented the lightbulb (he didn’t). With millions of indigenous people living in the Western Hemisphere, Columbus was clearly not the first person to set foot in the Americas. He wasn’t the first explorer to sail to the Americas. He wasn’t even the first European to do it. You can’t discover something that people already know about and you certainly can’t discover a place where folks are already living.

As governor and viceroy of the islands he happened upon and claimed (and renamed) for Spain and for the Catholic Church, Columbus was nothing short of a tyrant. He viewed the indigenous people in the Caribbean as a resource unto themselves, sending several back to Spain after his first voyage as an example of what fine slaves they would make. Rape and sexual slavery. Forced conversion to Christianity. Pillage. Plunder. And always—always—under threat of extreme violence. He demanded tribute of gold and those who failed to meet their quota were violently punished; when it was finally determined that the islands did not have the wealth of gold Columbus anticipated, his ships’ holds were filled with indigenous folks to sell into the slave trade and thousands of others were forced into slave labor on plantations. While Queen Isabella ordered that “Indians of the Spaniards” not be enslaved, plantations rapidly grew as the dominant economic producers in the region and the insatiable demand for cheap labor fueled the explosion of the horrific transatlantic slave trade.

Christopher Columbus was not an awesome human being. And before anyone gets all, “but America!” about it: he never set foot on the North American continent. And, no, Columbus Day isn’t a long-standing tradition here. The Knights of Columbus fought for a Catholic, Italian-American holiday and convinced Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt to establish such a holiday in 1937. Even then, the first recorded celebration of Columbus Day wasn’t until 1972.

A few years ago, The Oatmeal released comic detailing a good number of reasons why Columbus Day is a big, old pile of crap and suggested an alternative: Bartolome Day. When I first read it, I appreciated the sentiment but, upon further mulling it over, came to the conclusion that substituting a more sympathetic European colonial authority for an atrocious one is still kind of gross. I know that, as a society, we really love redemption stories and we really love white savior stories, so Bartolome’s story holds an innate appeal for many folks that want to do away with honoring Christopher Columbus. Ultimately, though, that story still centers European subjectivity and denies the experience and agency of indigenous people, except for when it moves the white savior’s plot forward. Basically, switching out one European for another is Columbusing the experience of the people of color that were the most harmfully impacted by the so-called “Columbian exchange.” Tempting though it may be to root for Bartolome Day, I feel the need to channel Nancy Reagan:

Instead of grasping at things to celebrate, I think that we should spend October 12th—or whatever day set aside to commemorate the anniversary of Columbus’ landing in the Americas—reflecting on the real history of European exploration and imperialism. We should take time to trace the historical roots of the current conditions faced by indigenous peoples globally. The reflection I’m advocating for isn’t meant to be an exercise in making white folks feel shame or force white folks into claiming some kind of personal responsibility for the horrors of the past—that would once again be centering a Eurocentric subject and, honestly, it doesn’t do a lick of good with regard to the actual problem. What I’m advocating for is a time to learn, to become more aware, and to look for constructive ways to put that awareness into action because, while we cannot claim responsibility for the past, we do share responsibility for the now and for the future.

Leave a Reply