Hello. My name is Jess and I am depressed—like, treatment-resistant, major depressive disorder kind of depressed. I was first diagnosed in 2002, during my freshman year of college. I had been battling with depression for years and years before I was formally diagnosed. I think saying that I have been depressed for three decades is a pretty accurate estimate. I am in therapy and I am on multiple antidepressants and, yet, here I am. Co-morbid with my major depressive disorder are multiple anxiety disorders, C-PTSD, hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia, and I am autistic—all of which can be contributing factors for depression to be treatment-resistant.

Me: trying to be actively engaged in my own life and enjoy things

My depression and 2020

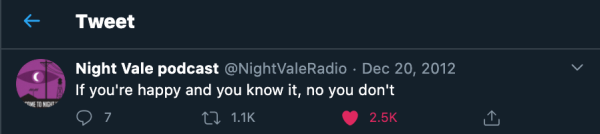

I am spilling my guts to you, dear reader, because October is Depression Awareness and Education Month and I have believed for a long time that talking about our personal experiences with our mental health issues is vital to disrupting and ending the stigma around mental illnesses. Now, before I move on, I need to make clear a few things that often come up in discussions about and contribute to some of the stigma around depression. First, depression is not just feeling sad. I know, especially on the internet, a lot of folks—myself included—engage in hyperbole to make a point: when I trip over something and stumble, my go-to line is, “I tripped and almost died.” Clearly, I did not almost die—I’m just using hyperbole to express that moment of fear when I stumble. Similarly, there are some folks who will use “depressed” as a hyperbolic stand-in for “sad” or “feeling down.” Please don’t do that. It adds to the ways in which depression is written off and not taken seriously, making it harder for folks suffering from depression to get the help they need. In fact, don’t do that with any mental illness: just because you like things organized doesn’t mean you have OCD; being startled isn’t the same as having a panic attack; normal worry about a stressful situation is not like living with an anxiety disorder. Just don’t do it.

I can. I know I can. I’ve seen me do it.

The second thing I want to clarify is this: do not give unsolicited advice, particularly if that advice shames taking medication. Yes; I have tried exercise, going outside, doing yoga, playing team sports, journaling, making art, going for hikes, going to therapy, going to group therapy, and just “pushing through it.” I’ve tried all of them in varying combinations. And, no, I’m not going to try some bizarre diet because a) don’t police other people’s food choices and b) I am poor and likely cannot afford whatever all-organic, non-GMO, turmeric-laden foods you think I should be eating. You know what does help? My medications. Yes, I am still depressed but I am much better able to cope with my depression with my handy-dandy Lexapro and Wellbutrin combination. To be blunt, taking my antidepressants makes me less likely to want to kill myself—those medications are literally saving my life. So, to recap: no unsolicited advice and no medication shaming.

The questionnaire used by almost every doctor—the PHQ-9—captures and measures symptoms of depression but it does little to capture the experience of depression. One of the questions on the PHQ-9 that I struggle to fill out is “How often, in the last two weeks, have you experienced ‘moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or the opposite; being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual.’ First of all, unless someone tells me, I have no idea what they’re noticing about my behavior. Second, I definitely experience sluggishness but mostly internal—as far as I can tell, I’m moving and speaking at the same speed I normally do. Then again, I’ve been depressed so long, maybe external sluggishness is my normal. In any case, that internal sluggishness is because one of the less discussed symptoms of depression is its negative effect on cognitive function: depression takes a toll on memory, information processing, decision making, cognitive flexibility, and executive function.

This is an excellent description of executive dysfunction and why I am writing these very words, right now, on the day of my deadline for submission, despite how much I enjoy writing.

“Trouble falling/staying asleep; sleeping too much” and “feeling tired or having little energy” are such benign descriptions for what I experience. I am tired all the time. A lot of that time, including right now, it feels like there are weights on my eyelids; it takes enormous effort to keep my eyes from closing. Even if they were to close, though, there’s a high likelihood that I wouldn’t be able to sleep. My depression and my fibromyalgia are a tag team that constantly attack my sleep: pain keeps me awake, depression and fibromyalgia cause fatigue, the fatigue makes my pain worse, I try to sleep because I am fatigued but the pain keeps me awake. Additionally, one symptom of fibromyalgia is disrupted sleep cycles. I always feel like I am submerged in a vat of molasses, trying to eke my way to the surface for air. Needless to say, I nap a lot but most of those naps are like putting scotch tape over a crack in a dam.

“I just came out to have a fun time and I honestly am feeling very attacked right now.” – chardonnaymami, Tumblr

I wanted to highlight the experiences of living with the cognitive function impairment (executive function and cognitive flexibility, in particular) and the overwhelming fatigue because these are some of the things I’ve noticed that strain relationships. Generally, when mental illnesses and chronic physical illnesses, I prioritize the experiences of those who are ill over the experiences of their loved ones because the folks who are ill are the ones experiencing—bodily, emotionally, and psychologically—the symptoms of their illness. That said, I know that those illnesses do impact others. I know that underlying issues can be laid bare by the stress of being mentally ill or loving someone who is mentally ill. And, in my experience, a lot of the strain on relationships is due to not being aware of what the mentally ill loved one is living through—if you don’t understand the kind of fatigue someone who is depressed is experiencing, if you don’t understand the ways in which depression impacts cognitive function, then you run the risk of assuming that your loved one is just lazy or a f*ck-up or self-centered or any number of other things. And assumptions like that hurt everyone in the relationship.

Trust me, we’ve got this line of thinking covered. We don’t need your help about it.

Because 2020 has been …2020, a lot of folks are experiencing additional psychological strain and depression is one of many mental illnesses that are on the rise. Though it is best to consult a mental health professional, you can screen yourself for depression online. As we continue to see a mental health fallout from the pandemic and other mass trauma events in 2020, we are all going to need to lean on one another and try to be understanding and empathetic. It is important that we, as a society, start taking depression seriously and acting with compassion. Please, take the time to listen to folks with depression, offer them a safe and non-judgmental space. Honestly, one of the best things my friends and chosen family have done for me, with regard to my depression, is simply accepting me as I am right now: they don’t ask me to cheer up, they encourage me but without judgment, they listen—10/10, definitely recommend. (Thanks, y’all!)

dinosandcomics

And, hey, to my fellow depressed folks, remember:

Leave a Reply