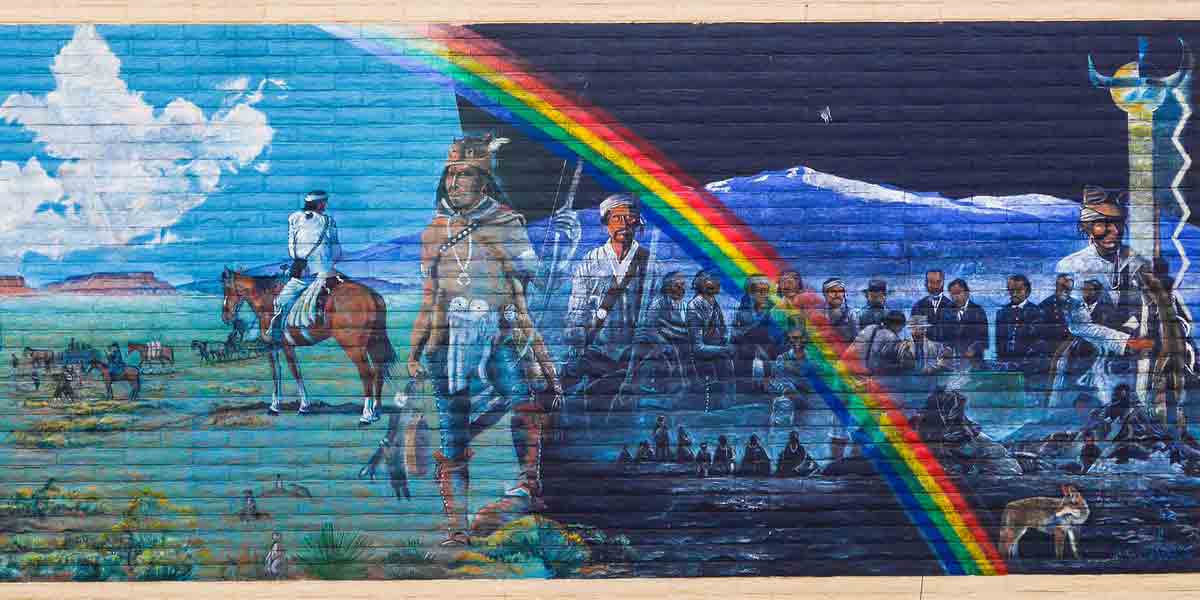

Lead Photo photo credit: Jay Galvin

Indigenous Peoples’ Day, though not yet universally accepted or observed—is not a new idea: the first recorded declaration of such a day was in California in 1939. That initial declaration used nomenclature best left in the past, calling it “Indian Day” which is rather problematic. In 1968, still in California, a resolution was passed and signed to observe “American Indian Day” on the fourth Friday in September—the fourth Friday in September is now a Californian state holiday called Native American Day.

Photo by Andrew James on Unsplash

In 1989, South Dakota’s state legislature passed—unanimously—a bill proposed by Governor George S. Mickelson that made Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a state holiday, declared 1990 a “Year of Reconciliation” between Native Americans and whites, and replaced Columbus Day with Native American Day. It was that adoption of Native American Day in South Dakota that marks the beginning of a formalized celebration of Indigenous people, cultures, histories, and legacies in place of Columbus Day—a day that glorifies a man that brought devastating cruelties to the Indigenous people in the Americas (CN: rape, murder, extreme violence, mass suicide).

Christopher Columbus is in the bad place

Indigenous Peoples’ Day—still known as Native American Day in South Dakota—has been widely adopted across many cities and state in the United States, though only South Dakota and Vermont actively practice non-observance of Columbus Day. Columbus Day, though variably celebrated since the late-19th century, is a rather new federal holiday having been established in 1968—which coincides, mostly by chance (I hope), with the increase in activism among Native Americans around the ongoing damage the United States inflicted upon Native communities. First proposed in 1977 at the International Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas, the move to eschew Columbus Day and replace it with a day honoring Native Americans picked up steam in the 1990s, when the Bay Area Indian Alliance organized a conference to develop and implement counter-quincentennial programming highlighting Native Americans’ five-hundred years of resistance since “Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

Rather than monstrous asshole who wanted a quicker way to exploit other people and their labor than sailing all the way around Africa but also didn’t want to sail through Muslim-controlled waters, it is the agency of Native Americans to resist, to advocate, to fight in the face of white settler colonialism that Native Americans and allies are celebrating today. A significant way for non-Native Americans to observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day is to seek out histories of Native Americans told by Native Americans. It is important for us non-Native Americans to learn about Indigenous civilizations and cultures in a way that de-centers colonizers because the continued lack of wide-spread knowledge perpetuates the damage done to Indigenous people. Highlighted recently by #NoDAPL, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in the US and Canada & #MMIWG2S, and disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths, the collective trauma settler colonialism has visited upon Native communities is brutal and ongoing—this is known as Indigenous historical trauma, a cumulative group trauma that spans generations. Over and over again, our government has stripped Native tribes and nations of land, of cultural knowledge, of opportunity, of means for self-sufficiency. It is these conditions that continue to put Native Americans at risk in so many ways that white people are not; it is also under these conditions Indigenous people have fought and are fighting for continued cultural and physical survival.

“Indigenous protectors were met with dogs, tear gas, and security forces today at the pipeline construction site, as the company tried to sneak in equipment, despite a pending ruling from a judge. One dog “got loose” and attacked several activists. Because of these actions this group of brave warriors just set up a new camp at the pipeline construction site to guard against against further deceit.” – Photo credit: Joe Brusky

All too often neglected in history text books, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas are frequently thought of as monolithic: how many tribes and nations can you name? I think most white people (we are the perpetrators of settler colonialism, so I’m calling us out specifically) would think we’re doing well to come up with ten or fifteen—usually the nations and tribes that parks and city streets are named for, a few from our history classes, and some us from nearby reservations. In reality, there are plethora tribes—including the 574 federally recognized tribes currently in the United States—each with their own cultures, languages, histories, spiritual traditions, identities, and—post-Columbus—methods of resistance woven throughout time and across physical spaces. One of the best and easily accessible tools to demonstrate this is the Native Land Map, a Canadian, Indigenous-led project that allows you to enter a location and find out which Native tribes or nations whose land that was originally. This resource is an amazing jumping-off point for learning about the peoples who lived on and shaped the land under our feet before agents of settler colonialism ravaged the people and the land. The area in which I grew up had been the land of the Adena who were around from approximately 800 BCE to 1 CE, Shawandasse Tula (Shawnee), S’atsoyaha (Yuchi), and ᏣᎳᎫᏪᏘᏱ Tsalaguwetiyi (Eastern Band of Cherokee). I was born on land that once belonged to Jicarilla Apache, Cheyenne, and Núu-agha-tʉvʉ-pʉ̱ (Ute).

“Tohono Indian Women led the Tucson 2019 Women’s March with a show of strength, resilience and power. This woman’s sign said: My Mom, Sisters, Aunties and Grandmas are sacred. Her son was by her side.” – Photo credit: Dulcey Lima on Unsplash

Though 2020 has certainly complicated, if not completely scuttled, social events like festivals and powwows, there are still numerous resources for those looking to learn more about contemporary Native American traditions and issues and those looking for ways to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day; Indian Country Today has an extensive list of virtual programming. Vision Maker Media specifically supports Indigenous-created media featuring Indigenous people and stories; on top of providing information on the films they support and how to watch them, their website also has information and links for nine virtual events for celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Old Town School of Folk Music is livestreaming the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Concert Chicago. The Peabody Essex Museum is hosting virtual programming to observe the day, including a workshop on sustainable art celebrating the harvest season.

Photo credit: GPA Photo Archive

Today, I hope that all of us who are non-Indigenous will take the initiative to start learning more about Native histories and contemporary issues, to familiarize ourselves with Indigenous art, and to listen to storytellers. It is important that we educate ourselves about the generational traumas inflicted on Native American and Indigenous communities and it is equally important that we learn about the history of and ongoing methods of resistance and resilience. As always, the best path toward understanding, reconciliation, and reparations is for non-Native Americans and non-Indigenous people to move past stereotypes, beyond defensiveness and white savior complexes, and to listen. Let’s spend the day listening.

Leave a Reply