A friend once described me as “pink” and I wanted to punch her in the face.

She meant it as a compliment to underscore my sensuous approach to life. Dressed in flowy, maxi-dresses that ripple when I walk, I don’t leave home without wearing lipstick and perfume. I prefer to accent my nightstand and kitchen table with a vase of fresh-cut yellow, white, or pink roses when possible. I light a lilac or rose-scented candle each morning while bathing and dressing.

“You’re just so…pink,” she laughed while I curled my hand in a fist underneath the table.

Pink Politics

Color is political.

I don’t mean “color” in terms of race. Color is political because historically those in power determined what certain hues mean and who could use them. The European aristocracy passed laws from the mid-twelfth century to the early modern period dictating the use of color across social strata, according to Kassia St. Clair in her book The Secret Lives of Color.

“Color was a vital signifier in this social language,” St. Clair said. “Dull, earthy colors like russet were explicitly confined to the meanest rural peasants, while bright, saturated ones like scarlet were the preserve of a select few.”

Pink has not escaped political associations.

Initially used in the 17th century as a noun to refer to a color, “pink” derives its name from the “frilled edge of a flower.” Pink combines the brilliant eroticism of red with the creaminess of white. The color is associated with softness, romance, innocence, sweetness, and playfulness. No wonder pink is the color of vintage Cadillacs, cotton candy, cherry blossoms, flamingos, bubble gum and Hello Kitty.

First Lady Mamie Eisenhower was linked to pink when she wore a rhinestone pink gown to the 1953 inaugural balls. Coupled with pearls and full skirts, Mamie Eisenhower’s pink gown suggested a return to traditionalism and femininity after the rationing of World War II.

Pink “pussy hats” became the symbol of the reinvigorated feminist movement after the 2016 election of President Donald Trump. But even pink had its limitations as women of color pointed out that not all vaginas are pink.

Pretty in Pink

As a child of the 80s, I was predisposed to love pink.

Pink was the shade of my Holly Hobby comforter spread across my four-poster, white and gold canopy bed. It was my preferred shade of neon socks and t-shirts, portable radio, roller skates, and Trapper Keeper notebook. Ballerina-pink was the hue of my pointe shoes, dance tights, and the t-shirt that peeked out from Sonny Crockett’s white linen suits in Miami Vice.

My childhood love affair with pink came to an abrupt end in 1991. That was the year I graduated from high school and Pearl Jam’s seminal album Ten was released. Pink suddenly felt babyish and self-indulgent in the face of grunge and impending adulthood.

I eschewed pink in favor of traditional corporate colors like black, gray, white, and navy during my years as a political reporter and later as a state Democratic political operative. I wouldn’t have been taken seriously if I wore a shell pink dress to a press conference to grill lawmakers about the state budget or alternatively, to a meeting to discuss communications strategy for the upcoming election strategy.

I relegated pink to the nights and weekends section of my wardrobe. Or I tried to toughen up pink by choosing colors like raspberry, fuchsia or pair it with black. As my thirties drifted to my forties, I wanted femininity I just wanted it on my own terms.

Rethinking Pink

I recently found a photo of my mother and her prom date taken in May 1967.

As a couple, they are a study of black, middle-class elegance and social aspiration of the era. Mom wore a strapless, icy-pink, satin dress. A white, fur stole draped her shoulders. Her arms were delicately armored in white, satin, opera gloves. Subtle washes of frosted pink eyeshadow and lipstick cover her eyes and lips.

Her date wore a white tuxedo jacket paired with black pants and cummerbund. A cheeky black-and-white, polka dot pocket square peers out of his jacket pocket. A pink carnation worn on his lapel matches the sweeping spray of pink flowers on my mother’s wrist.

My mom and her date waged a quiet revolution during a time of intense political and social upheaval in the United States. While they didn’t march in civil rights protests, their dignity was reflected in the refinement of dress. Mom and her date didn’t need to declare their right to be treated equally, they embodied their fundamental humanity with grace.

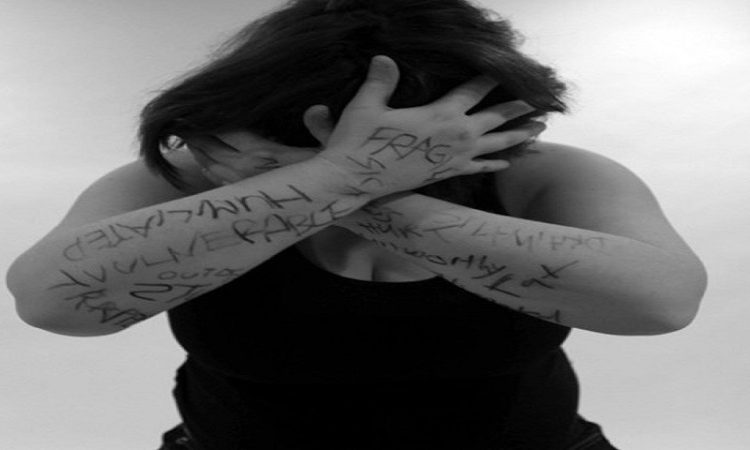

The photo reminded me that mom, until her death a few years ago, used femininity as a shield against the ugliness of life. Mom endured two husbands, the deaths of her parents and only sibling, and the changing times often draped in shades of pink. She wore pink pajamas while recovering from multiple bouts of cancer. Each morning mom sat at a gilded gold and glass vanity to apply her makeup, even if the lines of her black eyeliner and ruby lipstick grew squigglier with age.

Perhaps I have embraced pink at this stage of my life because it’s an artifact of our love. I write this while wearing a pale-pink linen dress I bought yesterday while visiting a handicraft store in Tulum. The laptop and cell phone by my side are encased in rose gold. Maybe my friend is right. I am “pink.” My mother would be proud.

Leave a Reply