Though his 90th birthday fell on this past Tuesday, today is the official observance of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. This day commemorating the life and work of Dr. King, though initially established as a federal holiday in 1983, was only just observed nationwide starting in 2000. Even the sanitized version of Martin Luther King, Jr. packaged and sold to me as a child, wrapped in platitudes and a day out of school, was still too controversial for some states to actually name the holiday after Dr. King until nineteen years ago. And that is, in no small part, because Dr. King was controversial; he was far more radical—especially in the last few years before his murder—than most of us were taught in school.

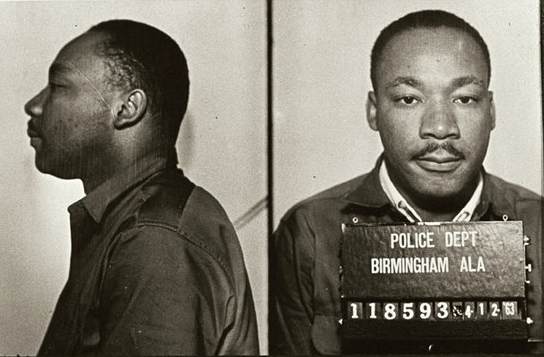

Source (x)

The whitewashed and sanitized version of Dr. King—crammed into the box formed by the one sentence from his “I Have a Dream” speech that the public remembers and wrapped in a ribbon made up of a complete misunderstanding of nonviolence as a political strategy—is often weaponized and wielded against those who engage in political activism, especially if those activists are Black. When protesters block traffic, disrupt political speeches, and rally in and around the halls of government, all too often pundits and politicians admonish that “Dr. King would not approve.” But those who would have us believe that Dr. King would condemn modern protest strategies rely on the word “nonviolent” without acknowledging the “civil disobedience” part of his tactics. Though not engaging in violence, nonviolent civil disobedience is, by definition, outside the bounds of the law (which accounts for many of King’s twenty-nine arrests); civil disobedience—violent or not—does not sit quietly, waiting for its turn to speak. It disrupts business as usual because business, as usual, has ignored an injustice.

Source (x)

Dr. Cornell West has said, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” So often, we conflate justice with the judicial system, collapsing the word into a synonym for a system that penalizes the poor, Queer people, people of color, and Indigenous folks. That way of thinking about justice ignores the fact that justice is also about truth, fairness, righteousness. Loving—truly loving—fellow people means treating them justly: being honest, being fair, acknowledging what is right and working to right the wrongs done. Dr. King’s philosophy and strategies, while not always ideal, were built on an idea of loving justice and just love. And it was that idea that precipitated his most radical positions.

Source (x)

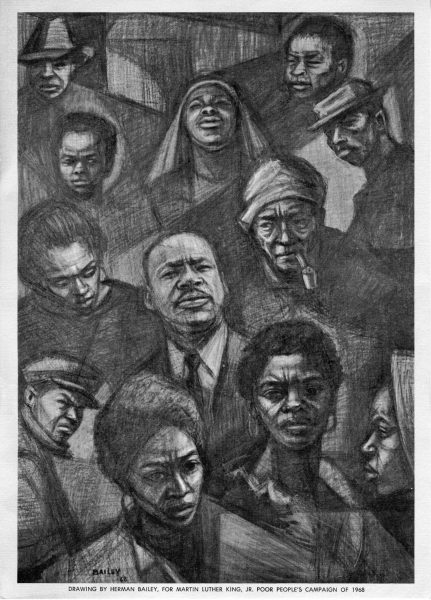

For all of the focus on Dr. King’s dream of children of all races holding hands—of mutual love and respect, of people being judged by the content of their character rather than the color of their skin—it is largely overlooked that he saw that goal being achieved by radically changing the system. As Brandon Terry pointed out, “King thought you would have to uproot the metropolitan boundaries and radically reorganize how we do schooling, municipal funding, mass transit, things like that, to bring about the kind of integration that he thought would be an ultimate good, and more properly facilitate justice in American society.” He fought for labor rights and laid the foundation of the Poor People’s Campaign (which has reemerged); he opposed the Vietnam War and militarization; he expressed grave disappointment and anger with white moderates “allies” who are now the folks weaponizing his sanitized legacy to quiet the organizers following in his footsteps; he advocated against capitalism.

By many he was considered an enemy of the state.

Source (x)

I bring these things up not just because I want all of us to better understand Dr. King, his philosophies, and his legacy. I bring it up because we are still fighting these fights. I bring it up because circumstances remain so dire for so many. I bring it up because, this past Friday, Nathan Phillips and other Indigenous people became targets of taunts and abuse when they stepped between white teenagers and the Black Israelis they were harassing. I bring it up because teachers are striking because public schools and their students are being failed by society. I bring it up because we are now on day thirty-one of a government shutdown that is hurting folks who were already in precarious economic positions. And I bring it up because police brutality against people of color—especially Black and Indigenous people—is still a problem of monumental proportions.

Source (x) Poor People’s Campaign flier – Kofi Bailey

We need Dr. King’s radicalism as much now as we did while he was walking the earth. We need radical love, radical justice. And I believe, as Dr. King did, that we will need civil disobedience to achieve those ends.

Source (x)

Source (x)

Feature Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Leave a Reply