Those who control the past, control the future. Those who control the present, control the past.

—George Orwell, 1984

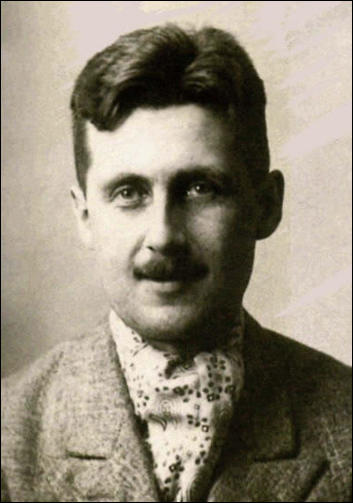

Eric Arthur Blair, the second of three children, was born on June 25, 1903 in Motihari, India. During the course of his life, Blair would form early friendships with poets and writers, join the Indian Imperial Police, do any number of menial jobs and taking to tramping around, work as a private tutor, a teacher, a literary critic, and as a journalist, volunteer to fight fascism in a foreign war (and survive a bullet through the neck), and write two of the most influential novels of the twentieth century—Animal Farm and 1984—under the pen name George Orwell.

Blair was born into a family heavily invested in imperialism: his paternal great-grandfather was the absentee-landlord of a Jamaican plantation, his father worked for the Indian Civil Service, his maternal grandfather made a living in speculative ventures in Myanmar. When Blair was a year old, his mother moved him and his elder sister to England and, save for a visit in 1907, his father remained in India until 1912. Though the Blair family had once been wealthy, his parents found they could not afford out-of-pocket the cost of getting him the education they wanted him to have—he wound up attending St. Cyprian’s School, Wellington, and Eton on scholarships. Worried that his grades at Eton—apparently, though active and participating in several publications out of the school, Blair’s academic marks left something to be desired—would not qualify him for a scholarship for university, his family decided that he should join the Indian Imperial Police. As his maternal grandmother lived in Myanmar, that is where he requested he be posted.

Source Blair/Orwell is in the back row, third from the left.

Blair served at several posts in Myanmar, working his way into the Superior Services with an appointment to Assistant District Superintendent, over the course of five years, at which point he contracted dengue fever and—already due for leave—returned to England to convalesce. Perhaps it was because of his experience during his school years of being treated differently because his family was not as wealthy as most of his classmates’, Blair had a difficult time reconciling himself with his place in the machinery of empire building; while recovering in England, he resigned from the Imperial Police and set his sights on becoming a writer.

Having been encouraged by a family friend to write about what he knew, Blair took it upon himself to investigate “certain aspects of the present” by “ventur[ing] into the East End of London—the first of the occasional sorties he would make to discover for himself the world of poverty and the down-and-outers who inhabit it.” Intermittently, he spent time immersing himself in the poorest areas of both London and Paris, using an assumed name, altering his dress, working assorted menial jobs and spending nights in common lodging houses, amassing information that would inform his first full-length book, a memoir: Down and Out in Paris and London. It was during this time that he began work on Burmese Days, while also writing for Monde and G. K.’s Weekly. It was while he was in Paris that he fell ill with the flu and was treated at a free public teaching hospital, an ordeal which he describes in the essay “How the Poor Die,” which was written not long after the experience, but was not published until 1946. Those years of research and immersion went on to influence nearly all of his writing—“In one or another of its destructive forms, poverty was to become his obsessive subject – at the heart of almost everything he wrote” until Homage to Catalonia, which was published in 1938.

Source Blair/Orwell is that tall son of a gun towering above everyone else.

After two years in Paris, Blair returned to England, where he spent his time writing reviews for New Adelphi and privately tutoring students. He went back to his periodic immersions in the poor communities of London, doing domestic work and working in the hop fields, documenting his experiences in his diary. Toward the end of 1931, he had twice tried to get his early version of Down and Out in Paris and London published, but was rejected on both counts. I don’t know if it was purely for the sake of research or if that decision was ever so slightly tinged with frustration about the rejections, in any case, Blair apparently decided to wrap up the year by deliberately getting arrested. He got well and truly drunk and was arrested on the charge of being “drunk and incapable.” Though it appears his stay in jail was shorter than he anticipated, he did still get an essay out of it: “Clink,” which went unpublished in his lifetime, but was adapted and included in Down and Out.

The following spring, Blair took a position as a teacher at a small private school in West London, where he taught for a year and a half before accepting a position at Frays College in Uxbridge. It became his custom while at Frays to take motorcycle rides through the surrounding countryside, until one such jaunt in 1934 led to a hospitalization for pneumonia, after which he never returned to teaching. The following year, though, would see two of his novels published—A Clergyman’s Daughter and Burmese Days—and his first encounter with his future wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy.

His next investigative project had him heading north to Manchester and investigating working conditions in the coal mines and the realities experienced by working class communities during the depression. While researching social conditions in Manchester, Lancashire, and Yorkshire, Orwell found himself attending meetings of the Communist Party; the book that would result from his time in the north of England, The Road to Wigan Pier, detailed both his findings and his ruminations on his political consciousness and his arguments for Socialism. This work landed him on the list of folks under surveillance by the Special Branch. He remained under surveillance from 1936 to 1948.

He and Eileen O’Shaughnessy were wed during the summer of 1936. The following December, having kept abreast of the goings-on in Spain as the country sped headlong toward revolution, Blair made his way to Spain to join the fight on the side of the Republic against the rising tide of Franco’s fascist/Falangist revolution. During his time fighting in the Spanish Civil War, Blair got caught up in the fighting between factions that supposedly fought on the same side, leaving him with a distinct distaste for Soviet-flavored Communism and a decidedly anti-Stalinist opinion. Finally, while at the Aragon front, Blair’s height nearly got him killed: he caught a sniper’s bullet to the throat, just barely missing his carotid. After treatment and convalescence, he was declared medically unfit for fighting—and, arguably, not a moment too soon, since the political atmosphere was rapidly changing and, in July of 1937, the group with which he was affiliated was becoming subject to purges, having been branded Trotskyists. Blair, quite reasonably, booked it back to England.

Back in England, Blair’s health failed to truly recover. After about a year home, he was hospitalized for what was suspected to be tuberculosis. In the fall of 1938, he and his wife made their way to then-French Morocco to wait out the English winter. While in Morocco, he wrote Coming Up for Air, which was published the following summer. Before long, though, the Second World War was in full-swing and, no longer being medically fit for military service, Blair struggled to figure out how to participate in the war effort—spending his time writing essays for Inside the Whale and writing reviews for a number of publications—, until he joined the Home Guard. Blair finally obtained “war work” when he was hired on at the BBC’s Eastern Service, where he supervised “cultural broadcasts” to India meant to disrupt attempts by Nazi propagandists to subvert the “imperial relationship” (which, for someone who struggled so hard with participating in the imperial machinery, seems hinky). He resigned after two years and focused his efforts on writing Animal Farm.

In 1944, as Blair tried to get Animal Farm published, he and Eileen adopted a child, Richard, and settled in Islington after having been bombed out of Mortimer Crescent. After getting a publisher for Animal Farm, Blair was approached about being a foreign war correspondent—an opportunity he had been hoping for, but was thwarted due to his health—and he left to cover newly-liberated France. While he was in France, Eileen went to the hospital for a hysterectomy and died under anesthesia. He returned to England for a short while and then headed back to the Continent, finally returning home to cover the 1945 general election.

The following several years saw Blair mixing his journalistic work for several publications with writing 1984. He chiefly worked from Jura during those years, accompanied by his younger sister and, later, his son, and Susan Watson, his son’s caretaker (though, Watson did not stay). He suffered a tubercular hemorrhage in early 1946, but hid his condition; later that year, he returned to London, working on his literary journalism and establishing George Orwell Productions, Ltd. for tax, legal, and royalty purposes. He stayed in London through that winter, one of the coldest British winters on record; the cold combined with the smog of London did very little to help his health. When he returned to Jura, he made substantial progress on 1984, until a boating accident that further exacerbated his health issues. He was hospitalized and formally diagnosed with tuberculosis in December 1947 and was finally able to return to Jura in July 1948, finishing the manuscript for 1984 in December. He made his way to a sanitarium the following January.

While 1984 was published to great acclaim, his health continued to deteriorate throughout 1949. He began courting Sonia Brownell that summer. Very soon after announcing their engagement in September, Blair was moved to University College Hospital; their wedding took place in his hospital room on October 13, 1949. By Christmas of that year, his health was in rapid decline again and, then, on January 21, 1950, an artery in his lung burst, killing him at the age of 46. He had specifically requested to be buried in the Anglican tradition, but no churches in London had space in their cemeteries—David Astor, editor at The Observer and longtime friend, lived in Oxfordshire and secured a plot in the graveyard at All Saints’ Church, where Blair was interred with a headstone that makes no mention at all of his famous nom de plume.

A democratic socialist, an outspoken anti-fascist (one who definitely put is money—and body—where his mouth was), a gifted writer, a man dedicated to documenting and illuminating social injustice, and a keen political mind, Eric Blair—George Orwell—left an indelible mark on the world, shaping the cultural imaginary through the bulk of the twentieth and well into the twenty-first centuries. He continues, nearly seventy years later, to remind us of the dangers of authoritarianism, to remind us that “if [people] cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them,” to caution us against complacently accepting living in a surveillance state, and that “no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it.”

Happy one-hundred and fourteenth birthday, Eric Blair! Thank you for your voice (even though it scared the bajeebus out of a lot of us). And I’m sorry that some folks still refuse to heed it.

Leave a Reply